Visualizing uncertainty: the effect on human cognition, emotion, trust, and decision-making

Conference

65th ISI World Statistics Congress

Format: CPS Abstract - WSC 2025

Keywords: communication, decision-making, trust, uncertainty

Session: CPS 85 - Data Visualization and Communication in Statistics

Monday 6 October 5:10 p.m. - 6:10 p.m. (Europe/Amsterdam)

Abstract

In everyday life, people frequently see predictions about the future for various topics, e.g. related to climate, economics, and health. These statistical predictions are often used in decision-making, but such statistical estimates are intrinsically imperfect and inherently uncertain, and decisions based on highly uncertain predictions are riskier than those based on certain predictions.

Although policy makers often take uncertainties into account in the decision-making process, there is no consensus on whether to inform the public about uncertainty as well. Even though this information can be crucial in decision-making, some fear that it causes negative psychological responses such as heightened risk perceptions and a reduction of trust, where the strength of the response probably depends on a person’s trait.

Our study: Visualisation of direct and indirect uncertainty

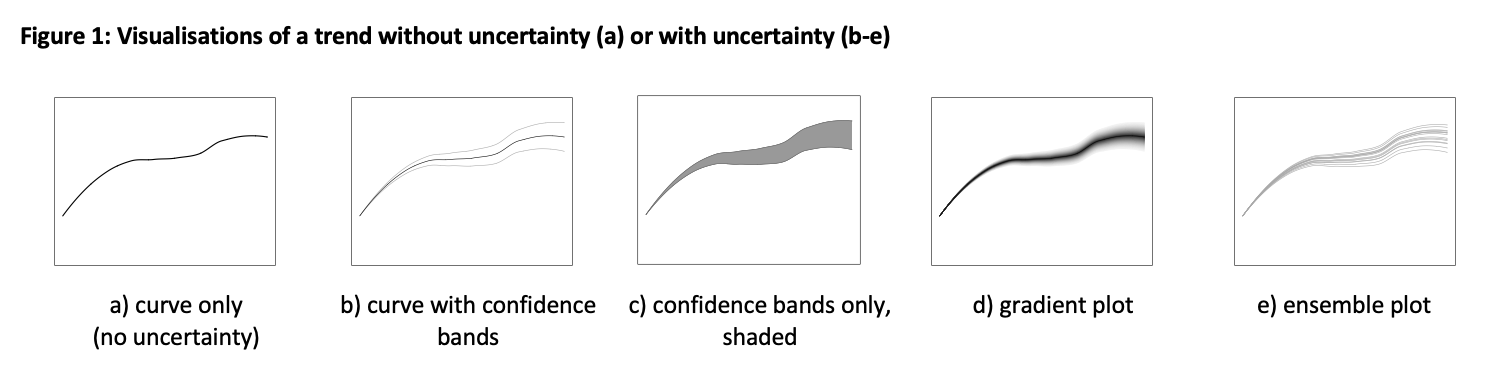

Research on uncertainty typically focusses on comparing numerical and verbal formats. However, little research has focused on examining the impact of communicating uncertainty in visualizations on people’s cognitive, emotional, trust, and behavioural responses. For instance, uncertainty in line graphs can be displayed in various ways (Figure 1b-e), but systematic research on how people respond to and understand these formats is lacking.

In our study, we focused on so-called epistemic uncertainty (unknowns due to lack of information) which so far received little attention in research. Additionally, we made the distinction between direct uncertainty (quantifiable; about the fact, number, or scientific hypothesis) and indirect uncertainty (qualitative; quality of the underlying knowledge). In the case of indirect uncertainty, we focus on a situation in which the experts’ certainty of a prediction is mentioned along with the visualisation.

Summarizing, we studied the effect of communicating uncertainty in different sources (direct vs. indirect), visualization formats (Figure 1b-e), and magnitudes (low/medium/high uncertainty) on people’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioural responses. Additionally, we assess the effects of individual differences like sociodemographic characteristics, numeracy, and risk attitude.

This was a large-scale study, using a panel of over 5,000 participants that is representative of the population of the Netherlands. Hence, our results are generalizable to the Dutch population and can therefore be implemented by national institutes that communicate statistics. Quite possibly, these results also generalize to populations of other countries, in which case the guidelines can also be adopted by their national institutes.

Results:

The first analyses of the data show that, generally, communicating either direct or indirect uncertainty does not change the receiver’s attitude towards the numbers, nor their trust in the number or the institute communicating them. This is good news, as a lowered trust was one of the main concerns for national institutes to communicate uncertainty. Additionally, the mentioning of an expert’s uncertainty about a number (indirect uncertainty) seems more influential than only visualising it (direct uncertainty). Furthermore, all visualisation methods to visualize direct uncertainty are understood as intended, showing that most people understand even the more complicated plots.

All results, including additional results concerning the effects of individual differences like numeracy levels and risk attitudes, will be discussed in more detail during this presentation.

Figures/Tables

Figure1